By Marti Zuckrowv

By Marti Zuckrowv "I'll write about women and their bodies," I announced

to my husband. I'm a woman, I have a body, and this

body of mine has messed with my mind for most of my

life. Or, is it my mind that has messed with my body?

"You are not your thoughts," an anxiety therapist

lectures my anxiety support group. "You are the person

who observes your thoughts."

And I think, so how did all this obsession with being

thin invade the person who observes my thoughts?

Society certainly reinforces this obsession for

so many, many women (although statistics show that the incidence of

anorexia nervosa among men is growing.)

This person who observes my thoughts was a dancer.

Let's get real. Standing in front of a mirror six

days a week for hours at time fueled the "never too thin"

madness.

And from the dance world I leaped right into the fitness

industry. Oy vey, was I in trouble then. And not only me.

I looked around and saw through the eyes of the person who

observes my thoughts a parade of women, all sizes,

shapes, ages, all suffering because of their particular

bodies -- too fat, too tall, small boobs, flabby belly,

you name it. And the women like myself, working in the

fitness industry -- whoof!

Granted there are some sane fitness professionals,

but in my 25-plus years in the industry, I saw many

colleagues struggle with eating disorders and

the unrealistic body image goals they chased after,

often at the expense of their physical and mental health.

I saw how the emotional pain of hating your body can

play out.

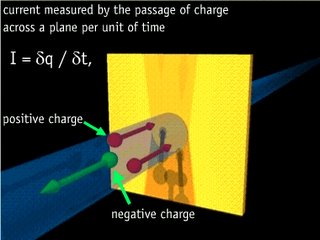

Like a parasite, the self-hatred enters you and flows

through your blood to the darkest deepest pockets

of your being; it lodges in your internal

organs. From there an octopus-like creature claws at

your flesh. You itch and burn from the inside out with

the shame of your flesh, your body. Then you pick up

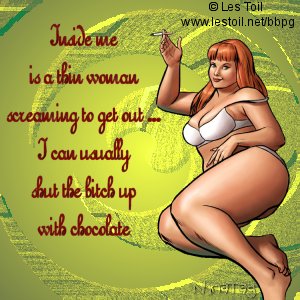

a magazine and stare at the perfect-size-six on the glossy

page, perky hair, perky boobs, milk-and-honey

complexion and of course she is surrounded by gorgeous

trim men.

Or you catch one of those car ads, the sexy car with the sexy

bimbo behind the wheel, triceps and biceps pumped up

just enough. Or maybe it's the fashion page, the

streamlined little-nothing dresses barely covering the

20-year-old model. There is no way out here if you

buy into this and so many of us otherwise rational,

bright, women do.

"Dance on Paper" was the last dance performance I did,

as a dancer and choreographer. I was coming out as a

writer, and hoping to get away from the fixation on

the thin body. Ha. In my early 50's at that time, no

matter how far I got from the tyranny of the dance

world, I was most certainly possessed with the hatred

of my female body, a perception I had unknowingly

accepted as the

TRUTH.

The person that I am could not get away from

the thoughts that I was observing, the self-destructive

notion that thin is beautiful, fat is shame.

These thoughts shot me like poison arrows. They left

large gaping holes in my arms and legs and belly. I sought relief in

the company of my demons. They hosted a party and lured

me with desire.

Starve, exercise, purge that body of

yours, you can do this. We will hold your hand and

when your fingers become twigs we will snap your neck

and blind your eyes to that ugly image in the mirror.I baby-sit my grand niece three days a week. She is

six months old. What I find so amazing is the

instinctive need to eat. There are no eating disorders

here. When she is hungry she cries for food. When she

has had enough she is done. There are no binges here.

How does it begin, this debilitating behavior, this

obsession with our bodies the way we think they should

look. We are not our bodies in the same way that we

are not our thoughts. Then what are we? How come we

get trapped in the body and the mind and do not really

live as who we are whatever that is.

Am I making any sense? What sense can I make of the jail so many

women inhabit? Self-inflicted? To self annihilate, just turn on the

tube, go to the movies, ask your mother. You can never

be too thin or too rich. Who started this conspiracy

and who had the genius to hypnotize half the American

population with such a mantra? I can't address the

rich part, I'll never know and luckily I avoided that

devil thanks to my leftist upbringing. But the other

half, I swallowed whole. Thanks to an amazing

behavioral medicine clinic with an exceptional eating

disorder program, I hope to soon be free of the

tyranny of anorexia. I'm working hard on my recovery

and let me tell you, it's rough. But I'm not giving

up. I choose life.

Oh yes. And words.

I choose words, to get me through.

Writer Marty Zuckrowv, of Oakland, California, is a lifelong dancer and performance artist who teaches movement classes to people with disabilities.

By Cecele Kraus

By Cecele Kraus