By Alan Rowland

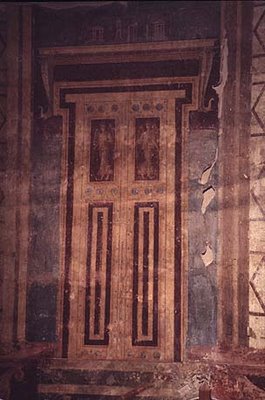

By Alan RowlandThe door stood at the end of a long, dark hall. It was closed and locked to all prying eyes and curious minds. I was afraid of the chipped paint and broken pediment, as though it might crumble and splinter to sharp pieces on the bare floor below.

No one ever mentioned the door or what lay beyond its insistent silence and dust. But silence may speak, and dust may cover a secret. The light of day through high windows and reflected off even higher mirrors never reached the door in its quiet darkness. No sound echoed from footsteps misguided to a wrong part of the church-like house. A pet never investigated; children showed no interest.

The door was merely 'there' - mute, imposing, with the threat -- or promise-- of something unknown.

To start it was only a door, but it became THE DOOR over time, as I grew to manhood. 'Curious,' I thought, and the door remained shut, locked and unpainted throughout years of painting and repainting the rest of the house. Eventually an armoire was lifted and dragged ungracefully down the long hall to cover the door, until it faded in mind, like old, stained wallpaper.

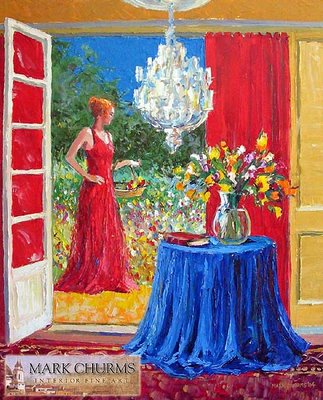

The house was an imposing structure, lovingly restored across a family's years to its original gothic beauty, with every modern convenience of the day. My mother fancied she had 'taste': 'That's one thing I always had,' she would boast, 'taste...eclectic, but taste.' The house was a testament to her modern sensibilities and style. The high-ceilinged rooms were painted a warm white, as a perfect environment for a mid-century modern decor, one that had seen its day pass, and return again to fashion, an affirmation of mother's 'good taste.'

The main rooms were large and connected to one another by French doors, with glass always sparkling. Twice a week mother would have 'help' come in for $45.00 a day. She would do her 'spot cleaning' each night before 'the help' would come to help keep up with a demanding, old house. Mother loved color, or 'colour,' as she might spell the word.

Textured color, vivid 'atomic' prints that even a child could love; color on drapes, upholstery and in the Picasso, Braque, and Cezanne prints that covered the walls - even in the 'commode', as I imagined she thought of it. Faded Persian color washed the floors, and rich, ceramic color lined shelves throughout the kitchen. The old Zenith color T.V. was banished to the huge kitchen, the obvious hub of the house, especially for the children.

Textured color, vivid 'atomic' prints that even a child could love; color on drapes, upholstery and in the Picasso, Braque, and Cezanne prints that covered the walls - even in the 'commode', as I imagined she thought of it. Faded Persian color washed the floors, and rich, ceramic color lined shelves throughout the kitchen. The old Zenith color T.V. was banished to the huge kitchen, the obvious hub of the house, especially for the children.It could have had 'rabbit ears,' but I might be imagining that. My brothers and I each had our own spacious room. I, the youngest of six, was relegated to an old butler's pantry in the long forgotten servant's quarters, nearest THE DOOR. The room had one Gothic window, with its four walls a platoon of closets and shelves, lined up neatly and ready for God's battle with the Infidel. A generation grew, with Dad and then, tastefully, Mother 'passing on,' as people used to say.

I inherited the house, as the sibling closest by - my brothers spreading out across the country, indeed the world. I moved to the heart of the house, and married within a year of my mother's death. Another generation began. My beloved wife Emily and I bore three sons, if you counted the first -- still born. Our hearts broke, until later, with hearts aglow, Emily gave birth to those two sons, five years apart. They were like twins.

They looked alike and spent all their time together, exploring the house and sharing its mysteries.

They looked alike and spent all their time together, exploring the house and sharing its mysteries.The armoire, dragged so awkwardly to hide the door so many years before, had never left its spot as sentry. The door, now in its second generation of memories and buried under six coats of Benjamin & Moore's Linen White, held its silence, kept its secrets.

My sons raced together into manhood. We lost the first in a pipeline explosion in Kuwait, and the second on his first night's deployment in Iraq. The deaths shocked us to the core, and seemed to happen overnight, "...and then there were none."

Emily's sadness slowly killed her; an aching, gnawing grief that embraced a loving heart and turned her soul black with pain and anger.

And then there was one. Me rattling about a house too large for me, too full of memory and grief; my own faith slowly ebbing. Consulting my brothers around the world, we agreed finally to sell the house and its furnishings - lock, stock and armoire at the end of the dark hall.

My gay friend Arthur leapt with flamboyant joy at the prospect of owning the house he had coveted in secret for... forever. He, weary of 'all those dusty, old putti,' as he put it, a confusion of Gothic and Renaissance architecture, ripped the house to its old bones. As each Gothic detail was rudely torn from the house, I seemed to lose one more vestige of the faith which had brought me a peace across the years.

Soon my faith had deserted me to but once a year, watching Cecil B. De Mille's "The Ten Commandments" on High Definition TV, and getting a tickle of 'faith' - until monday morning. Arthur's demolition of the prized Gothic house slowly worked its way up flights of stairs, down halls and into rooms all barely even recalled. Finally the wrecking ball and hammer found their way to the top floor and my room as a boy, blessedly left alone.

Arthur's armoire, now 'one old painted whore, with too, too many facelifts,' would turn her last trick.' Arthur would need my help. It's amazing what the efforts of two men at opposing ends of enthusiasm can accomplish. Arthur played 'HRH Elizabeth I' and I reluctantly feigned obeisance. Fifty years of a Mother's 'gift' for 'tasteful' color and 50's 'Buck Roger's' wallpaper, peeled off in huge sheaves, as though they were fleeing the door. Arthur trilled with pleasure.

We used scrapers and hammers. We used a clever gadget that removed rusted screws from their old iron foundry tombs. The lock and three hinges were removed with much difficulty, and just a bit of melodrama. The door was finally, irrevocably free from its prison, and it toppled like the Titanic in two giant slabs. We leapt back and waited for the huge dust storm to clear and reveal... nothing!

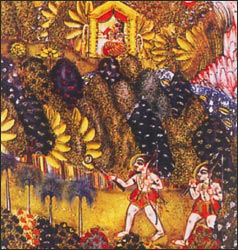

The door collapsed in a groan to reveal insulation and pipes, and cables for the Zenith and HBO. The insulation revealed older insulation and some older than the last. Arthur tore at the insulation, the newer a 'Pink Panther' pink; the older - damp and faded in some moldy, spectral brown/grey. Scotch taped to the oldest of the insulation was a page torn from an old newspaper bearing the image of Siddhartha, sitting cross-legged beneath the Bodhi tree. His eyes, once heavy with kohl, were now heavy-lidded, in acceptance of Nirvana.

The door collapsed in a groan to reveal insulation and pipes, and cables for the Zenith and HBO. The insulation revealed older insulation and some older than the last. Arthur tore at the insulation, the newer a 'Pink Panther' pink; the older - damp and faded in some moldy, spectral brown/grey. Scotch taped to the oldest of the insulation was a page torn from an old newspaper bearing the image of Siddhartha, sitting cross-legged beneath the Bodhi tree. His eyes, once heavy with kohl, were now heavy-lidded, in acceptance of Nirvana.The figs of the Bodhi tree lay rotting at the feet of his frail body. Next to this fading page was taped another, a gravure picture of the smiling Buddha,

fat with promise and good luck. Some Chinese newspaper was crumpled into balls on the floor, behind the door that led nowhere. It had never occurred to Arthur to wonder why the door was there. 'It'll make such a fab niche,' he said, and if fact were told, I had to agree with him.

fat with promise and good luck. Some Chinese newspaper was crumpled into balls on the floor, behind the door that led nowhere. It had never occurred to Arthur to wonder why the door was there. 'It'll make such a fab niche,' he said, and if fact were told, I had to agree with him.I never did find the real truth about the door myself. But I came to believe my - our - first born, still, lifeless and mute as the door itself, had the answer. He might have had all the answers.

And then, there was one.

Writer and artist Alan Rowland lives in southern New Jersey. For many years, he worked in New York City as an illustrator and art director until a seriously debilitating illness robbed him of the use of both hands. Five years ago he moved to the countryside in southern New Jersey, where he began to write poetry and prose about health, illness, art and loss.

1 comment:

What a lovely, poignant story. It brought me to tears.

Post a Comment