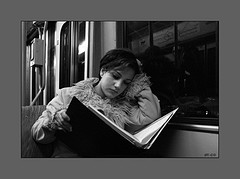

Marti Zuckrowv, of Oakland, California, begins a monthly column today.

Marti Zuckrowv, of Oakland, California, begins a monthly column today.My mother hid chocolate bars in her closet. Not the

small bars, but those big, family size Hershey bars.

How did I know this? I was a snooper. Like most kids,

I longed to discover the secrets of who she really

was, and therefore, who I was. And another thing:

once I got my nerve up and climbed into the closet, I

felt protected from the rest of the world, as if the

billowy fabrics brushing against me were shields of

armor. I'd be safe.

My father shared that closet with my mother, but his

side held little interest for me. Boring gray suits,

a blue one for special occasions and the dozen or so

long and short sleeve shirts my mother ironed for him

on Saturdays when she returned from the laundromat.

I ironed his handkerchiefs, a chore I came to enjoy for the meditative quality of sliding a steaming iron

up and down the ironing board. Magically, the wrinkled

white cotton square stretched out and lay flat and

flawless, ready to be made into perfect quarters. An

imaginative child, I'd pretend I was this flimsy piece

of cotton. I'd let my body go limp; my arms sagging

like elephant trunks, my legs as wiggly as overcooked

spaghetti. I'd roll up sequentially, vertebrae by

vertebrae, my spine transforming from a horseshoe

shape into a young oak tree.

I'd do it again, and again, often adding choreography that included

creating grand arcs with my arm, the iron heavy in my

hand, the stream from the iron hissing in musical

accompaniment. Little did I know I was embarking on my

lifetime passion as a dancer. Needless to say, my

ironing chores took forever.

It was my mother's side of the closet, though, that intrigued me.

I'd sneak in to the closet when I came home from

school. Both my parents worked in Manhattan and didn't

get off until five so I had ample time to do my detective

work.

I'd slide the thin wooden sliding doors open, forever

intrigued by the novelty of sliding doors (all the

other closets had doorknobs with key holes beneath

them) I'd peek around the room, (just in case a

burglar or a murderer happened to be there) before

stepping in and leaning against the rack of her

clothes.

I'd press my face into her quilted pink

bathrobe. I loved the cool silky feel of the fabric

next to my skin and the faint scent of her Jean Nate

spray that lingered there. Like a caress, the soft

fabric comforted me when the waves of guilt at being a

snoop threatened to drown me. I'd imagine I was

Rapunzel letting down my long golden hair. My handsome

prince would arrive and carry me off to far away

places where we would live happily ever after.

I'd be safe from that bad man, Mc Carthy, who my parents and

their friends talked about when they thought I wasn't

listening. I'd fold in like a pretzel, hug myself

greedily, then extend my arms and legs to become as

large as possible in such a confined space. I'd feel

the transformation of my body contracting, expanding,

contracting expanding. I'd be free of this world and

enter the world of movement.

I'd found home. I'd poke around my mother's handful

of fancy dresses, her royal blue taffeta box like frock,

her wedding and bar mitzvah outfit, her rose colored

velvet dress with it's thick soft sash that tied

in the back and draped down over her broad hips,

a lime green silky shirtwaist with tiny pearl buttons, and my least

favorite, the black long-sleeved narrow dress she wore

to funerals.

That dress, when I spotted its darkness, got my heart racing.

The Rosenbergs. Maybe my parents were next. I'd will myself

to breathe, make myself as small as possible and scrunch down to

investigate the few boxes of high heeled shoes lined

up on the bottom of the closet. (That's where I'd find

the chocolate bars, stashed away in an otherwise empty

box.) I'd step into my favorite pair of black suede

pumps, secure them to my feet with the thick ankle

strap that wrapped around, back to front, and imagine

myself a flamenco dancer.

I'd uncoil my body, stand up and walk out of the closet.

I'd pose before the mirror over the dresser.

Taratata,

taratata, I'd suck in my belly, throw out my ribs,

arch my back, position my arms to frame my face and

snap my fingers.

Taratata, taratata, I'd whirl

and twirl, unsteady on the high-heeled shoes but

committed to my dance. I'd see the girl in the mirror

and know that was me, a dancer.

Writer Marty Zuckrowvia is a lifelong dancer and performance artist who teaches movement classes to people with disabilities.