By D. L. Luke

By D. L. LukeFriends of mine in the First Cavalry --Marcus, Spaghetti-O, Harry Lynk nicknamed "Missing," and I -- were excited that day. The mail had come from home.

A few days before Christmas, in 1968, we were no longer the FNGs in base camp, taking half 55-gallon drums out from under latrines and burning shit with diesel fuel. We were passed that point, yet leagues away from the code words that earmarked the pages of our imperfections in history: ‘White Christmas.’

I'd been the BS -- bullet-stopper, dipstick, dago -- names the old-timers used to call us -- in Vietnam three months, twelve days.

My girlfriend Mindy sent me a package and at first, I didn't want to open it. All I could do was smile at the smiley face sticker next to my name. All I could do was touch the crisp neat corners, the scotch-taped ends with the nubs of my fingers. The thrill would be gone once I opened it.

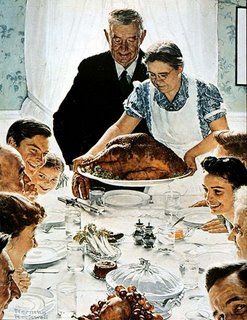

For breakfast, coffee, powdered eggs, and sausage links were served in mess hall. We sat around a table, smoking, sipping on piping hot coffee or Tang, waiting for everyone to get done eating so that we could open the mail. It was the only thing we had to look forward to in the day. Otherwise it would've been like any other day in compound, cleaning our M-16's, next to impossible to keep clean, drinking, feeling sorry for ourselves. We shot the shit about who's a mark and who's a number ten, and wrote letters to families and friends.

It felt like being a kid again finding gifts under the tree on Christmas morning. We opened our packages and displayed all the loot.

Joe Speglio, nicknamed Spaghetti-O, was nineteen years old, from Bensinghurst, Brooklyn. "Look, the latest Hendrix tape," he said. "Picture my old man, this little Italian wearing a shop coat with sawdust on his shoes. He goes into a record store and asks the salesman where he can find 'that Hippie's Voodoo music.' Cracks me up just thinking about it."

"I got Fruit-of-the-Looms and homemade chocolate-chip cookies," Marcus said. "Mom must've heard about us going commando out in the jungle. I guess she wants to make sure I have a fresh clean pair, just in case."

"Yeah, in case your balls get blown off and they have something to put 'em into when they carry you out in a body bag," Missing asked. "What you get Mahone?"

"A Christmas tree," I replied. "My girlfriend sent it."

No taller than ten inches, five inches in diameter at the base, the Christmas tree was made out of plastic. The batteries were beneath the bottom of the base. When you flipped the switch, the little tree's lights turned on. They were tinseled all different colors: reds, golds, blues, and army greens.

"Ain't that sweet," Missing said. "What you get her?"

"Nothing," I replied. "Didn't have time."

"Mahone's too busy with that redheaded dink chick," Marcus asked. "Where does little Miss Saigon Lucy get off thinking she can dye her hair red? It is dyed isn't it?"

I got up from the table, shoving Mindy's letter into the inside pocket of my field jacket. I pushed the chair back and picked up the tree from the base. "Don’t overfeed the housecats," I said, and tucked it underneath my armpit.

Barracks was dead. Close to noon and already it was jungle rot hot. At least, I'd get some peace and quiet. I took off my jacket and relaxed on my cot. I opened the letter, lit a cigarette, and started reading.

Dear Evan,

Freaky how it's that time of year again.

Doesn't feel like Christmas since you've been away.

Mom wants me to go with her in the

city and shop. She wants to see B. Altman's windows.

I told her to go with a friend. You know me, I don't dig crowds.

I miss you. Can't wait to see those baby blues of yours again.

Look at it this way, you should be grateful.

You don't have to eat those orange-sliced candies

Grandma hands out to all the grandkids. You know, the kind of

candied fruit that tastes like chewing on an amoeba.

Hope you like the gift. Write to me soon --

Love,

Mindy

My eyes followed the clean lines of her penmanship. I grew bored of reading and watched the faded blue lines draw flames as I lit the letter with my Zippo.

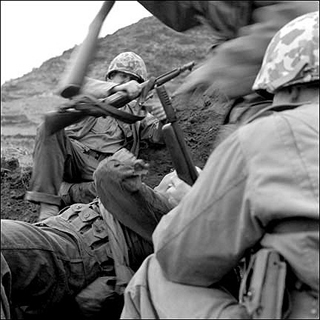

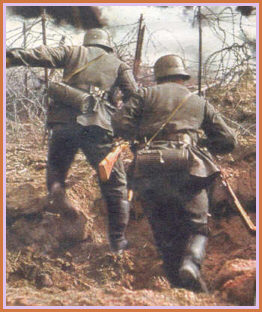

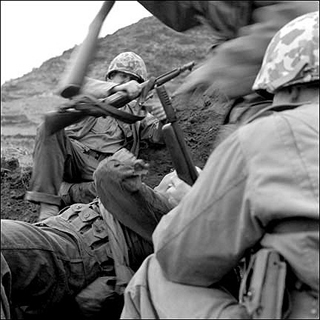

The next day we were sent out in the Central Highlands. To insure our troops nonviolent efforts, we endured another hellish walk in the yellow heat. We trudged through the swamps and marched across the wet, open rice paddies. If our feet got wet, we kept a change of wool socks on us at all times.

W

e swept the area for any booby traps and spider holes south of the Iron Triangle. The dense forest, beyond the dry flat land, was scarred hillside and bare mountains. Bone-dry sand sifted underneath my steel-plated rubber soles like sifting flour mom used to make piecrusts out of dough.

Pressing down into the small of my back was my rucksack. Even though the tree Mindy had sent me could not have weighed more than a few ounces that extra weight made a difference to the seventy-two pounds I was already humping.

Off in the horizon, the sun set a jaundiced color, the color of dead flesh hanging from the canopy of trees, the color of jackfruit. We picked a spot where we'd spend the night.

We dug our foxholes on Christmas Eve. I wanted to light the tree; but I couldn't do that. Hell, I couldn't even light a cigarette. If I lit one, boom I'd get my head blown off.

VC could see a burning cigarette a mile away. Even if I'd tried covering it by cupping my hands around it, taking a drag would make my face glow red.

We dug a foxhole extra deep. When we'd gone down deep enough I turned to Missing and said, "Put your poncho on top."

The foxhole was big enough for only one man at a time to fit. Since it was my tree, I went first.

I turned it on. The star had a mild brassy glow. Weehawken was the furthest place from my mind, but the energy coming from the string of lights reminded me of home.

For a brief moment, I forgot about the war, the fear that kept us surrounded. How the air smells like sweat, smoke, and white phosphorus. I took a step back and detached myself from what I’d seen: she’s just a kid, naked running down an old ox-cart trail with her arms stretched out burned from the napalm that had been

dropped on her village a few hours ago. "Nong Qua," she cries. "Nong Qua." ("Too hot").

The one emotion – longing to go home – haunted me in my dreams. In the waking hours, I fought back the feeling, which never lost ground inside my interior landscape, plagued with disorder and conflict. Yet there I was in the moment with Mindy. I pressed my head against the warmth of her American full-sized breasts.

The sensation slipped away into the fog that crawls along the land before the dawn disappears with sunrise. Through the fabric of the poncho, Spaghetti-O said, "What's he doing in there? Praying or taking a dump or something?"

I folded the poncho over and climbed out of the hole. "Everybody'll get their turn," I said.

From front to rear, from razor rash to gritty black face, a long line of men stretched across the entire length of the trenches. Atheist, Baptist, Buddhist, Catholic, Jewish didn't matter. They were all waiting their turn to see the Christmas tree.

As far away as I could get, I made my way to the back of the line. Those that had the time had already set up home. Canteens of water, C rations, letters, mags, mosquito repellent, helmets, sunglasses, and decks of

Bicycle playing cards invited temptation. With the mood I was in, I wanted to shuffle the cards around, scatter them into different decks, make a mess of things. Something soft and pink, the color of flesh tones caught my eye. Underneath a letter was a photograph.

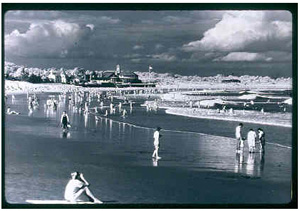

I picked up a snapshot of a foxy lady in a string bikini posing for the camera. She stood on a beach. Her face wasn't much to look at; but she had a great body. What I wouldn't give to be with her for five minutes. That's all the time I would need.

Frizzy-haired Detroit knocked the picture out of my hands. "What do you think you're doing, gawking at my wife like that?" he asked.

"I didn't know she was your old lady," I replied. "Man, you'll make everyone crazy leaving a thing like this around."

Point man, Chuck Reed, and his chipped tooth, the only injury he got for being on-point during his second twelve-month tour, had been the last one standing on line to see the Christmas tree. He overheard us talk. His hand snatched the photo from Detroit.

"She's a piece of ass, all right," he said. "I don't get why a woman like her would want to get hitched to Frazzle-head. It ain't fair."

No match to Reed, Detroit was the last soldier anybody wanted in his foxhole while under fire. The dumb fuck got in the way and jeopardized the welfare of others when terror came to kill and maim. Reacting in his usual pussy fashion, Detroit flipped out and threw punches like a girl. Chuck grinned a chipped-tooth grin from ear to ear.

They were about to go at it with each other when the company commander broke through the crowd. "Cut the crap," he said. "Before I write you both up."

Reed shoved Detroit into the wall of sandbags. He tore the snapshot in half and slung the halves at him. "Here, you can have your wife back now," he said. "I'm done with her."

Hours later, things began to settle down. Somewhere hidden in the lineup of men, Detroit waited his turn to see the Christmas tree.

The zone -- dense with a darkness that smothers the moon and the field of stars -- felt like being sealed inside a coffin.

It reeked of formaldehyde. It reeked of stinking dead bodies bloated from the heat. My guilty conscience reeked.

When you're away from home, living in a world of hurt, a world of shit that makes your worst nightmares seem tame you got compensated for certain things. Some guys dug booze; for others, it was drugs. I couldn't get into any of that. I loved women.

They were so easy to get. They were always right there. Hell, they'd send them out in the middle of nowhere out in the jungle. They'd come in army jeeps with rolled up mats.

I thought I loved Mindy. I used to worry about who she dated. If she was still a virgin or not. Now, I didn't care.

I never got crabs, the clap or any of those sexually transmitted diseases from fucking women. I figured I had nothing to lose; I’d take my chances.

Who knows why I couldn't get enough warmth from a woman, any woman. It didn't matter what she looked like or who she was -- so long as she wasn't VC. If she could give me warmth, affection and a little understanding, if she could make me forget where I was and the things I'd seen than I was happy, however brief it might've been.

The line of men waiting to see the Christmas tree had shrunk. It took all night, but everyone in my company, including the company commander, went down into the foxhole and looked at the five-and-dime tree on Christmas Eve.

Author D.L. Duke resides in Ithaca, New York and also writes as a journalist.

At the end of the day, the process is repeated. Eyes checking for stray, leftover makeup, making sure moisturizer is applied evenly, teeth are flossed. And for a split second, before she turns out the light, she steps back as if-this time-to really take it all in at once. But she hears an old echo, 'you'll do,' and instead give a half smile, shrugs, and turns away.

At the end of the day, the process is repeated. Eyes checking for stray, leftover makeup, making sure moisturizer is applied evenly, teeth are flossed. And for a split second, before she turns out the light, she steps back as if-this time-to really take it all in at once. But she hears an old echo, 'you'll do,' and instead give a half smile, shrugs, and turns away.