By Laura Stamps

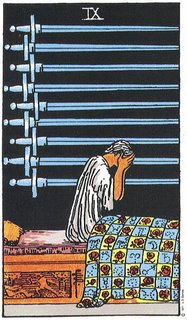

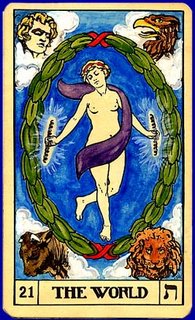

By Laura StampsRestless from her puzzling tarot card

reading, Ravena decides to drive

downtown and explore the neighbor-

hoods clinging to the mountains of

the city. Each narrow street hugs

the curve of a mountain, while drive-

ways shoot up at an angle or plummet

straight down. On the sloping side

of the street, mailboxes rise higher

than the roofs of homes that sprawl

large and spacious, most perched

on stilts, each with a wooden bridge

leading from the front door to the

road. High fences and thick masses

of trees and shrubbery surround the

mansions at the top of the mountains,

some resembling castles carved from

rock, painted in sunny pastel shades.

Winding through these mountain

neighborhoods, Ravena realizes

she must keep her mind focused

on the last tarot card, The World,

if she hopes to discern its meaning

in her life, to manifest its prophecy

of success and abundance. Quickly

she creates a chant for her intent:

“Wise Athena, thank you for your magic.

Open my eyes, guide this blessed chant.

Abundance and success shall manifest.

The World will bring me only the best.”

Wild onions bow their heads to the

setting sun as Ravena walks back

to her room after dinner, every step

a tonic for cramped muscles after

a long day of driving. Rain curtains

one of the mountains, and the dark

sky reflects the same shade of gray

she chose when painting the deck

last spring. Instantly, clouds part

for the sun, and a rainbow stencils

its bright hoop over the murky sky

in scarlet, tangerine, yellow, green,

blue, indigo, and violet, this looping

spectacle so wide Ravena finds

color variations smudged in between

the usual spectrum. For several

minutes the rainbow towers before

her, a perfect semicircle. One side

closed, the other forever open.

When she walks through the door

of her hotel room the telephone

rings. “I know you’re coming home

tomorrow, but I couldn’t wait,” Odell

says, his voice laden with misery.

“I feel awful.” Sitting on the edge

of the bed, Ravena asks, “Are you

ill?” Odell groans. “No, not really,”

he replies. “It’s just that everything

bothers me.” Ravena smiles, glad

he can’t see her expression. “Could

you do a healing spell for me?” he

asks. “Anything, please, I’m so tired

of this.” Ravena laughs. “It’s not

funny!” Odell shouts, frustrated.

“I know,” she replies, thinking about

The Star. “This reminds me of a

tarot card I drew last night.” She

reaches for her bag of magical tools

and unzips the top. “I’ll be happy to

cast a healing spell for you, Sweet-

heart,” she says. “Great,” he replies,

and begins to complain about his job

and the cats as he walks into the

kitchen to search the freezer for

a snack. “Honey,” Ravena says,

“we need to cover all the magical

bases.” She hears him open the

freezer door. “Before leaving for

work tomorrow, go into my office,

open my cabinet of magical supplies,

and find a short length of red ribbon,”

she says. “All the ribbons in there

have been blessed with holy water.”

Odell pries the top off a cardboard

container of soy ice cream. “Pin it

to your shirt pocket to ward off the

Evil Eye,” Ravena continues. Odell

scrapes the last spoonful of ice cream

from the carton and throws it in the

trash. “Okay,” he replies, smacking

his lips. “I can do that.” Ravena

smiles at his sudden cooperation.

“Then I’ll cast a healing spell for

you tonight, and you’ll feel much

better tomorrow morning,” she says.

“I hope so,” he moans. “Love you.”

And he hangs up. Ravena drags the

tool bag across the bed and turns it

over. She fills a tiny green amulet

pouch with a pinch of dried fennel,

geranium, rosemary, and lavender

for healing. Then adds five beans

and two charms, a silver hand

and a crescent moon, both power-

ful repellents of the Evil Eye.

It worries her that some people

possess the ability to send the Evil

Eye to another without realizing it.

“Odell has been cranky for so long,

who knows how many people

he’s offended?” Ravena mutters,

closing the amulet pouch with

a red cord long enough for Odell

to wear it around his neck, hidden

beneath his dress shirt and vest

every day. She places the amulet

on the bed and casts a sacred

circle, waving her wand over it

three times in a clockwise direction,

seeking the healing magic of Isis.

“I call on the power of Isis,

Great Goddess of Restoration.

Heal Odell’s troubled mind.

End the root of this strife.

Hide him from the Evil Eye.

Under your wings I place him.

Please grant my supplication.”

She thanks the Goddess and opens the

circle. Energized from Odell’s call and

the power she summoned for this spell,

Ravena rolls over on the bedspread,

closes her eyes, and pulls light from the

table lamp into her body, using it to relax

her muscles, until she dissolves into

a river of star-shine, the three tarot

cards dancing upon a mystical horizon.

READ THE CONCLUSION TO "THE THREE TAROT CARDS" on Saturday, December 2, 2006.

Laura Stamps (www.kittyfeatherpress.blogspot.com) is an award-winning poet and novelist. Over seven hundred of her poems and short stories have appeared in magazines worldwide. Winner of the "Muses Prize Best Poet of the Year 2005" and the recipient of a Pulitzer Prize nomination and six Pushcart Award nominations, she lives in South Carolina and is the author of more than 30 books and chapbooks of poetry and fiction.

At the end of the day, the process is repeated. Eyes checking for stray, leftover makeup, making sure moisturizer is applied evenly, teeth are flossed. And for a split second, before she turns out the light, she steps back as if-this time-to really take it all in at once. But she hears an old echo, 'you'll do,' and instead give a half smile, shrugs, and turns away.

At the end of the day, the process is repeated. Eyes checking for stray, leftover makeup, making sure moisturizer is applied evenly, teeth are flossed. And for a split second, before she turns out the light, she steps back as if-this time-to really take it all in at once. But she hears an old echo, 'you'll do,' and instead give a half smile, shrugs, and turns away.