By Karen Jahn

By Karen JahnNow of course atrial fibrillation is not fatal; some people don’t even feel it.

But for those of us who suffer from a metaphoric two boots on the chest, black spots before the eyes, and shrieking joints—all caused by insufficient oxygen in the blood, every day is another downer. Of course, as friends and acquaintances counsel, it won’t go on forever, but it seems forever as I lie here, the months and meds continue and the fib keeps returning.

A scary thing, this condition, for which twelve prescribed pills a day are required. And that is only the beginning. Calling doctors until there is no busy signal, being shunted around various extensions, each with a recording saying there’s no one to take your call right now, forced to listen to Strauss’s waltzes as I try to schedule still another lab appointment. That has become my lot as a victim of atrial fib. And if a reading of coumadin level (the blood thinner which prevents strokes) comes up too low, under 2, the four-week wait starts again, the next attempt to control the atrial fib recedes still another month, and stupor sets in.

A heart-beat is something I’d like to take as a metaphor, not an experienced event. Yet as the recurrences of atrial fib add up, I can’t help but feel that my body is prisoner to this short-circuiting organ. No matter what I do, what meds or procedures, my heart keeps breaking free and running as fast as a hummingbird’s wings. If that meant I could run, too, well then, I wouldn’t have a problem. But just staying upright is often a real challenge. No it’s not fatal in the sense that I’ll keep breathing. But in terms of being able to focus on anything else, well, that is coming to an end.

And so, using my Ph.D. and writing training, I’ve searched the web. On official cardiology websites of major medical centers it’s clear that because many people are asymptomatic and/or physically inactive, most patients with atrial fib are taken for granted. Unlike ventricular fib, etc., atrial fib is not fatal. No sudden cardiac arrest, in fact, the heart can’t stop running. X percentage of

folk achieve some stability from cardioversions, Y percentage from cardioversion and antirhythmic meds, but many of us find that within two weeks of this treatment, the heart leaps up, not to behold a skylark, but to embrace tachycardia and atrial fibrillation.

folk achieve some stability from cardioversions, Y percentage from cardioversion and antirhythmic meds, but many of us find that within two weeks of this treatment, the heart leaps up, not to behold a skylark, but to embrace tachycardia and atrial fibrillation.There’s another fix, called ablation, but some doctors, including my electrophysiologist, believe it is still in the experimental stage. He advises me to keep trying these meds until we find one that works and postpone ablation until the technology makes the procedure safer. But the stories of ablations working, posted on medical websites, are well, heartening. One story, of a man who had just climbed Kilimanjaro, having had a successful ablation which freed him from decade-long invalid status, made my day. So I tell my doctor, and my insurance company, that I’m more than willing to take the risk. I want to try to land in the 80% of patients whose ablations are successful. I am someone who, until this condition began, used to work out seven days a week. I want to be that person once more; it would be good for my heart!

Do I sound like I’m obsessing? Oh yes, I believe that’s one of the greatest costs of any illness that is not fatal and not easy to correct. No one else really listens to your symptoms, or tries to find a cure. Instead it’s protocol as usual even if it doesn’t fit. If I know the difference between supraventricular tachycardia and (left-side) atrial fibrillation, I get better answers for my questions.

A friend and fellow writer has begun to revise her life: to change she sees it as a small patch of sand with a blanket and an oasis nearby.

She then imagines that one day she will awaken to discover other places, maybe some of them vernal, to set her blanket and begin a new life. Given the frustrations I’ve had so far with my atrial fib condition, I’m beginning to reconsider my patch of sand. So I couldn’t go to the sports friendly cook-out suggested for the Fourth of July. I’m not being a martyr--not being able to stand for more than two minutes means I would be beside myself at such a party.

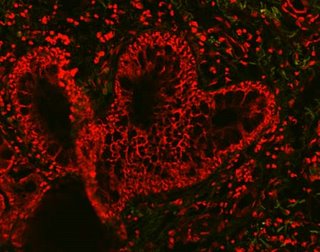

Instead, I busy myself here at home with writing, reading, listening to music, talking, and singing--all things I love. My glass is not half empty, I rehearse to myself; I still have the life of the mind. I just try to imagine waking each morning able to leap out of bed, and walk with no dizziness. Each time I wake from being cardioverted—those electric paddles on the chest that shock one’s heart back into sinus rhythm—I have that euphoric experience: I have my normal heartbeat back! I turn, I see the monitors: 55 beats a minute, a steady horizontal and vertical line on the ekg, and plenty of oxygen everywhere.

Karen Jahn is a retired English professor, amateur tennis player, novice singer, and writer living in Columbia County, New York. Her memoir, “Transitions”, is in process.

2 comments:

Hi Karen, this is really a fine fine piece. Send it elsewhere, expanded? Thank you so much for writing it, for letting MyStoryLives publish it. And I hope you find the solution SOON, so that the heart beats RIGHT!

love,

Claudia

Hi Karen, this is really a fine fine piece. Send it elsewhere, expanded? Thank you so much for writing it, for letting MyStoryLives publish it. And I hope you find the solution SOON, so that the heart beats RIGHT!

love,

Claudia

Post a Comment