"She didn't expect Antonie to summon her to the hacienda that morning and she certainly didn't expect to kill him in his bedroom that night. Even an hour before she sank the blade into his throat, she would have denied it possible that she, Sister Renata, could end her cousin's life, that she, a nun, could cast aside the sixth commandment and perform the frightening and horrendous criminal act that occurred.

But she did cast aside the sixth commandment, THOU SHALL NOT KILL, and she did kill him."

That is an excerpt from the murder scene in

That is an excerpt from the murder scene in , the scene called at one point, "Bloodbath," and later, renamed what it is now, "Roseblood."

This scene is pivotal. This scene convinces a judge and jury back in 1883 to convict Renata of murdering her cousin. Murder in the first degree. This scene gives new meaning to the word FRAMED.

This is the scene that lands her and me in prison.

So who wrote this scene and when exactly was it written?

That depends on your point of view.

You could say that I wrote this scene on May 3, 1997.

Or you could say that Antonie wrote this scene on September 3, 1883, not long before he died. You could say he wrote it as a way of framing his cousin.

Who wrote it depends on how you look at fiction, and at writing. It also depends on the notion of "self," and the nature of the "I," that is, the "I" who is writing.

Writing fiction is tricky business. It's all about writing in made-up voices. Voices that feel so absolutely real that they come to life.

My son Noah who is home for a while needed a book to read the other day and so I gave him Nicole Krauss' The History of Love. If you haven't read it, I would highly recommend you do. Nicole Krauss was perhaps 30 years old, a gorgeous young woman, when she created the absolutely mesmerizing first-person voice of a really cranky old man named Leo Gursky.

If you haven't read it, I would highly recommend you do. Nicole Krauss was perhaps 30 years old, a gorgeous young woman, when she created the absolutely mesmerizing first-person voice of a really cranky old man named Leo Gursky.

If you haven't read it, I would highly recommend you do. Nicole Krauss was perhaps 30 years old, a gorgeous young woman, when she created the absolutely mesmerizing first-person voice of a really cranky old man named Leo Gursky.

If you haven't read it, I would highly recommend you do. Nicole Krauss was perhaps 30 years old, a gorgeous young woman, when she created the absolutely mesmerizing first-person voice of a really cranky old man named Leo Gursky. Here is how the character Leo Gursky speaks, as he is "channeled" through Nicole Krauss:

"When they write my obituary. Tomorrow. Or the next day. It will say, LEO GURSKY IS SURVIVED BY AN APARTMENT FULL OF SHIT. I'm surprised I haven't been buried alive."

I've read a ton of fiction in my day but I don't think I've ever read a more convincing first-person narrative than the one created by Nicole Krauss in Leo Gursky. When I first encountered that narrator (the story was excerpted in The New Yorker before it was published as a novel) I kept thinking, it's impossible, she couldn't have created this old guy, could she?

But she did. Like I said, fiction is a tricky business.

Fiction comes alive in our minds because of the magical power of words (I published a piece on this topic before.) Words create pictures in our minds. If I say, "dark pine trees make silhouettes against a milky blue sky," chances are you get an image in your mind.

A fictional narrator is a made-up thing, yes, but if it is good fiction, like Krauss' (or even if it's not so good,) then the words create strong pictures, and the voice feels as real as this "real" one that I am using, writing write now.

We are swept up by the voice and the narrative. We are swept up into the action and carried off to another world, where we are delighted to reside for as long as the book lasts. While we are reading, we are completely immersed in something enjoyable; we have, if you will, our own private narrative movie going on inside our heads. If we really, really love the book, we kind of dread it ending.

Indeed, writing in The Atlantic in November, 2008, Yale psychologist Paul Bloom (his article "First Person Plural" is

about happiness and the "self" and suggests the notion that we have multiple selves or identities with different and often conflicting goals, fascinating!)

reminds us that "the most common leisure activity is not sex, eating, drinking, drug use, socializing, sports, or being with the ones we love. It is by a long shot, participating in experiences we know are not real -- reading novels, watching movies and TV, daydreaming, and so forth."

To become immersed in a fiction, Bloom asserts, we must adopt the fictional "self" of the narrator.

For sure, writers are completely hooked on this "drug" that is our own minds spinning great fantasy worlds out of words! I know I have been many times.

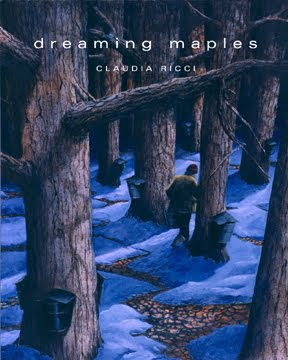

It took me years to disconnect from the characters who inhabited me, and my first novel, Dreaming Maples.

I lived so closely with Eileen and Audrey X and Candace for so many years as I was writing and rewriting and editing this multigenerational novel that I just couldn't stop thinking about them when it was all done. I loved these characters almost as though they were members of my extended family (actually when I think about certain members of my extended family, I am quite certain that I liked my characters a lot better. :)

Detaching from the characters and the images of the novel proved difficult, as it does for many writers post-novel. I just couldn't stop missing them! For a good long while, i

t was kind of like I had

"empty (book) nest" syndrome.

I couldn't stop "being" in the lovely Vermont sugarbush full of grey maples and sunny blue skies, the spot where the novel takes place.

The same sort of thing is true for readers. Characters often feel so real to us that they make us cry or laugh. We are delighted in their heroicism, delighted in their triumphs, sad or even angry at their losses and defeats. When we really care about characters, we can get into very heated arguments and debates about them, in book groups and in classrooms or even with friends and acquaintances, just having a cup of coffee.

Often we get into arugments over whether a character acted in the right manner. We can argue about whether or not a character should or should not have done what she or he did. No matter that what the character did, and what the character is, is simply, words on a page.

What matters is that the literature is alive in our minds. In this way, what we read really does matter, because it affects the way we think about our lives, and our moral choices, and the moral choices that others make.

Often I turn my classroom into a kind of jury; I tell the students that we are going to discuss, just the way jurors do, whether or not a character behaved "appropriately." Or ethically.

It makes for great discussions because, of course, the first thing you have to discuss is what it means to act "appropriately." Who decides what is appropriate? Who says what is right and what is wrong?

Another thing I do in my classroom is I have all the students, not just the "creative writers, write fiction.

When I tell my college students that they are going to write fiction, many of them get nervous.

They look at me, and they shake their heads and they say, "No, I can't possibly do that. I cannot write fiction. I'm not at all creative like that. I don't write stories. I can't write fiction. Please don't do this."

And then I smile and I say, "OK, you can't write fiction, but can you tell a lie?"

At which point, my very street-smart students (most of whom come from New York City where they have grown up in impoverished neighborhoods) smile and laugh and say "well of course, everybody can tell a lie."

OK, I say, then let's tell some lies. Let's tell the most convincing lies that we can tell. Let's fool everybody with our lies.

And then we practice, by "lying to tell the truth."

We play a game in the classroom where each person has to write down two truthful statements and one lie about themselves. The goal: to fool each other. We try to make the lies so convincing that nobody can tell the difference between the truths and the lies.

And that's exactly what good fiction does.

And what is so funny, is how good

most of us are at lying.

Antonie was so good at lying that he got his poor cousin convicted of murder.

Well, that's true, IF you believe Sister Renata's version of things.

In Chapter 21, in her diary entry, Sister Renata supposedly told "the true story" of how her cousin Antonie

died by his own hand. It was a pretty damn gory story. And it a was pretty damn convincing one too.

But now, when you read the murder chapter that follows here, the chapter in which Sister Renata supposedly kills Antonie with a straight razor,

I bet you'll think that this chapter is convincing too.

The point is, it all depends on

point of view.

In fiction, point of view is EVERYTHING. If you can convince readers that you are an old man named Leo Gursky, then more power to you.

But then, think about it. THE SAME THING IS TRUE IN LIFE. Have you ever had a family story that was in dispute? Have you and your family members ever told the same story from very different points of view? We do this exercise in class too. We tell the SAME FAMILY STORY from different points of view.

In our family, there is the very famous piano lessons story.

My dad insists and has absolutely no doubt that he wanted me to take piano lessons and that I was a rebellious kid who refused, growing up, to take them.

And me? I just know absolutely that my dad is wrong. I just know that I was DYING to take piano lesssons but that my dad -- for money or other reasons -- refused to let me take them.

Is he right or am I? It all depends. Is he writing or am I writing? It depends entirely on who is telling the story.

In our post-modern, internet-drenched age, we see more clearly than ever that truth is a very relative and fluid thing. The so-called "master narratives" that used to give life "meaning," are fast disappearing, if there are any left at all! I am thinking of "master" narratives like this one: there are two sexes in the world and they are clearly and very separately defined, and one member of each of these sexes falls in love at some point with the other sex, this being his or her soul mate, and said couple gets married in a service reserved just for heterosexuals, and they procreate and they live happily ever after. End of story.

Uh, know any other stories?

What we now realize is that most of those master narratives -- about sex, race, gender, etc. -- were social creations, creations of our language and culture and biased points of view.

What we now realize today is that reality is really just a creation of our (collective) minds. Reality is a kind of word picture, that we share (or don't share, consider the raging hoopla over the word "MARRIAGE.")

The "truth" of something depends to a very large extent on who is telling the (his) or her-story.

Who, for example, tells the history of the "discovery" of the New World? If it's Columbus, and subsequent white colonizers, as it was for eons, then, God save us, and save the Indians who perished.

But if it's the Taino or some other Native American population telling the story of how indigenous populations were decimated by colonization, well, then you have a whole different story.

In the post-modern notion of "intertextuality," everything in the world is a TEXT. Including history. Including our SELVES, which are really just a collection of word-based memories. (For a wonderful exploration of how our selves "disappear" without our memories, read Oliver Sach's amazing book, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for A Hat.)

Anyway, back to fiction. What does all this business of intertextuality and post-modernism have to do with fiction?

Everything. Every single thought you have, is a word creation. A projection. And not only that. Every thought you have is a kind of story. A made-up story about how things are, moment by moment. Or even more accurately, how you perceive things to be.

Why this fascinates me is because it has everything to do with whether or not we are happy.

If we tell ourselves depressing stories about ourselves, and others, and the reality around us, chances are that the world around us will be depressing.

But if we flip the switch, and tell ourselves upbeat and positive stories, well, then we are likely to be happier and have happier outcomes in our lives. (If you doubt this, try reading some of the emerging literature on mindfulness and positive psychology.

Read Martin Seligman's book, Authentic Happiness, or ex-Harvard professor Tal Ben Shahar's book, Happier. (Or just enroll at SUNY Albany this spring semester and take my Happiness class, and you'll read these and a whole lot more.)

Meanwhile, try this little experiment, it might make you happier, or at least give you some important insights.

Start this exercise by thinking about somebody you would like to kill.

Or at least, try thinking about somebody who makes you very very angry. Or very very resentful. Or very very sad.

Think about a highly charged argument that you've had with this person.

Or think about a situation with that person that makes you furious. Think about something that happened with this person that makes you as angry as you can possibly be.

Now try this, if you can. But I'll warn you, it isn't easy -- I try to get my students to do this in writing classes all the time and some just sit there and stare at their notebooks. They cannot write a word.

But go ahead and give it a try: try to flip the story.

Try, just for a moment, to step into the shoes of THE OTHER PERSON, and try to tell the story from your opponent's point of view. Try to fit yourself like a sock into that shoe -- that person that you hate, that person who makes you murderously angry or resentful or sad or whatever -- and feel the situation. Go over every single event, from that person's point of view, feel every bit of emotion that your antagonist feels. Try to feel WHY that person feels what he or she feels.

If you do it, I promise you that you will not hate the person you hate quite so much as you did.

Or at least, you will have a much better insight into why they behave or feel toward you the way they do.

This is one of the exercises that we are going to do this upcoming semester in my Happiness class, we are going to "Flip the Script." We are going to take some of our journal writing, writing in which we detail all the emotional pain that we have in our lives, and we are going try to get people out of the endless ruminations that trap them.

We are going to try to stop telling the same old stories, the stories they tell in therapy -- my mother did this to me, my father did that to me, etc. etc. -- and we are going to try to turn it into fiction. Fiction that flips the script. Fiction that transforms the energy of the pain and makes us moves forward, to get somewhere more peaceful with these personal dramas that hold us back from happiness.)

I had three students in an independent study (a test run for the Happiness class) this past fall and the results of this "Flip the Script" exercise were remarkable. My students found themselves telling stories from "other" points of view and having huge insights into their lives.

All three students (upper division psychology majors) said that they found the exercises remarkably helpful and useful.

OK, so back to Antonie's murder. And his supposed framing Renata for his murder. (I promise you will get the scene shortly.)

Like I said at the start, I (Claudia) first wrote this scene on May 3, 1997. I wrote the scene in one fell swoop and then I brought it upstairs to the third floor and I read it out loud to my husband Richard and to my son, Noah, who was then only seven years old. (Amazing to think I have been writing this stuff for most of my son's life. Ayayayay.)

Anyway, a crazy thing happened immediately after I finished reading the murder scene out loud. According to the diary entry I wrote that morning,

May 3, 1997: "mybodymindsoulspirit is drained by all this writing about blood and murder. Ifeel CRAZY and caved in, and anxious and agitated and I hatethe feeling. Today when I read the first murder scene to Rich, Noah saidhe hated it, and a female cardinal crashed against the window. Yesterday, a red grosbeak, I haven't seen one in eight years, it has a bib  of red like bloodon it, well, I saw one yesterdaymorning and today too."

of red like bloodon it, well, I saw one yesterdaymorning and today too."

of red like bloodon it, well, I saw one yesterdaymorning and today too."

of red like bloodon it, well, I saw one yesterdaymorning and today too."I remember that cardinal crashing into the window,  and a few minutes ago, I went upstairs and reread the diary entry to my husband and he says he remembers it too.

and a few minutes ago, I went upstairs and reread the diary entry to my husband and he says he remembers it too.

and a few minutes ago, I went upstairs and reread the diary entry to my husband and he says he remembers it too.

and a few minutes ago, I went upstairs and reread the diary entry to my husband and he says he remembers it too.

How strange that reading that chapter about blood and gore and murder would have been immediately followed by a red cardinal crashing against the bedroom window?

(As I posted this stuff this morning, it occurred to me that windows have frames, and my book has frames, and things keep getting FRAMED.)

The cardinal crashing against the window was a very very weird weird coincidence.

When I first started writing this version of Sister Mysteries, this kind of coincidence was cause for a big hoohaw.

But now, considering all the coincidences and convergences that have been occurring since I started writing Sister Mysteries (and the nun story, Castenata) I am honestly no longer a bit surprised at this or any other "coincidence."

I know now that this is just the way things go writing this book.

OK, finally, time for the chapter. Except for one thing: I never typed that particular chapter into my new laptop. So now I have to do that.

And as that Chapter (called "

Roseblood")

is really part of Castenata, which is the nun story, it belongs in that blog.

So here you go, CHAPTER SIXTEEN, of Castenata!

P.S. Happy New Year, with strong emphasis on the word HAPPY!

No comments:

Post a Comment